"Relatives and friends on one hand exhorting those on the other side, each thinking about their lives and property, other than their conscience; and then Crimson (Catholic) and the White (Protestant) gowns separated, most of them with tears in their eyes."

-Francois de la Noue, at the peace-talks of Toury, 1562

Welcome friend, to the page that asks, "Rome or Geneva, or Wittenburg"?

---------------------------

Contact us

The Perfect Captain

---------------------------

Flags, Uniforms and Fieldsigns of

The Huguenots

The Admiral's Sash

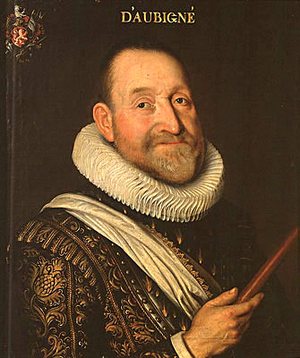

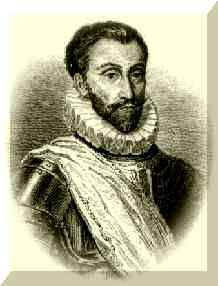

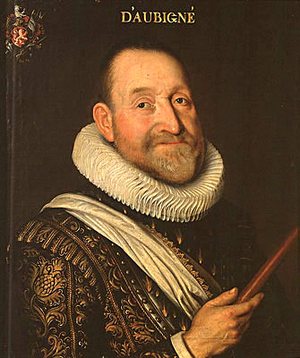

This painting of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny-Chatillon is an excellent starting point. Why is Gaspard de Coligny, one of the main leaders of Protestants in France, wearing a sash, and a white one in particular? Understanding this is the key to flags, uniforms and fieldsigns of the Huguenots throughout the Wars of Religion in France (1562-1598).

Origin of the Sash

In his Memoirs, Francois de Scepeaux, Sieur de Vielleville (later Marshall) claims that sashes were a foreign importation and unheard in France, first seen by him at the Siege of Metz during the later Italian Wars. He states that the Spaniards wore Red, and the Germans, yellow sashes. When speaking of the Huguenots years later he goes on to say that they first got the idea from the Reiters that they hired in the first war (1562-1563). Since the Huguenots had this fieldsign before their Germans reached them in late 1562, this is unlikely, but it does show that this was an innovation.

Why was it white?

Lancelot Voisin de La Popelinière, a Huguenot officer who served in the wars, had this to say about the sash (or scarf) in his 'Histoire de France': [commenting on how the battle of Dreux lasted until dark] "I could scarcely discern between the Admiral's (men who) wore white scarves with the red his (Catholic) enemies wore". To explain why white was chosen, he said the Huguenots selected this color “To mark them well and to show a clearness of conscience and their intention to maintain the honor of God and the public (weal)". It is tempting to assume that "Protestant white" was adopted because of the leadership of Louis Bourbon, Prince de Conde. The colour of the Bourbons was indeed light yellow (close to white), and this may have been a factor in the choice. However Popelinière's statement is corroborated by both Agrippa D'Aubigne in his 'Histoire Universelle' and Marshall Gaspard de Saulx, Sieur de Tavannes (a Catholic) in his 'Memoires'. Denise Turrel, in her book 'Le Blanc de France. La construction des signes identitaires pendant les guerres de Religion (1562-1629)' states categorically that the choice of white was a political statement (of innocence and good motives), just as red was a statement by Catholic soldiers of their loyalty to the crown. Wearing the colours of a particular noble house would have been seen as rebellious and partisan, something the Protestants were desperate to avoid (See John Calvin's 'Institutes', book IV Chapter 20, item 32). There were abberations; the Gendarmes at the battle of Moncontour wore yellow-and-black scarves to honour the German Duke of Zweibrucken who died leading his Reiters and Landsknechts into France that year (he was a staunch ally).

Who wore the Sash?

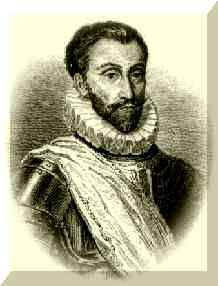

As seen above, the Admiral is shown wearing it, and he is mentioned by Popliniere as having it at Dreux. In the contemporary engraving shown here, we can see that Conde is wearing it at the battle of Jarnac where he was killed. Both Aubigne and De La Noue mention wearing it themselves. Aubigne even claims that King Henri III wore one to honor some Huguenot regiments that rescued the town of Tours from the forces of the League, during the period he was allied to Henri of Navarre. Certainly Navarre, later King Henri IV of France wore the white scarf, not only making it his trademark symbol, but one which all French officers of both religions would wear for the next 100 years.

How did the colour white and the sash affect Huguenot uniforms?

De La Noue in Book One of his Memoirs recounts the story of the truce for the peace talks at Toury in 1562, the last hope of avoiding a full scale war. "Relatives and friends on one hand exhorting those on the other side, each thinking about their lives and property, other than their conscience; and then Crimson (Catholic) and the White (Protestant) gowns separated, most of them with tears in their eyes." This was not an aberation- as has already been stated, white was an important statement for the Protestants. But did they all wear white?

It is certain that the Gendarmes did. It is again universal in the artwork; Protestant cavalry are in white coats, hence the name 'Millers' given to them by their enemies. The sash seems to have been the marking of an officer, worn over his armour, but the white coat worn over the armor is the uniform of the heavy cavalry. Ordonnonnce Gendarmes companies were since the 1540's (renewed in the 1570's) commanded to wear plain Cassocks (sleeveless coats with faux sleeves hanging in the back). The only acceptable decoration was borders around the edges of whatever colours they liked (often their own livery colour). The main colour was to be that of the Captain's livery. So when the Protestants took up white, it wasn't a different type of uniform- it was just the Gendarme companies switching colours.

The white coats lasted at least until the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre in August 1572. After this date loyalty to the crown became less hotly defended by Protestants. Duplessis-Mornay and others wrote against tyranny with shades of Republicanism in their writings. Henri de Conde aimed at creating a Protestant Protectorate in the south and west, really a separate kingdom. This was also the period of the Politique movement, where moderate and (and malcontent) Catholics joined Huguenot armies, and would not likely wear Protestant colors, regiments being raised separately but serving in the same army. It is likely that while the white coat did not disappear, it was no longer required. Bethune (Sully) mentions fighting in an Orange-Tawney coat at Arques. While the white casaque is not mentioned after the sixth Civil War (1577), the Huguenots continued to strive for unifromity and to avoid ostentation as much as possible.

Why the Sash is the key to understanding Protestant flags

Catholic armies are routinely shown beneath flags displaying the Cross of St. Denis. Protestant armies are shown universally under flags with a bend from the upper hoist canton to the lower fly canton. Why is this this. The Cross of St. Denis was worn by French armies in the middle ages as a national identifier, usually on a red background. This appeared on flags and on coats regualrly before the Italian Wars. Just before the Wars of Religion it was coming back into vogue. When the Civil War broke out, royal forces immediately took it up as their own. As we saw above, the Protestant symbol was the sash, worn from shoulder to thigh. This "bend", a common heraldric device was visually transfered to the flag, hence both sides had their symbol.

A brief study of the Protestant army in the French Wars of Religion, 1562-1598

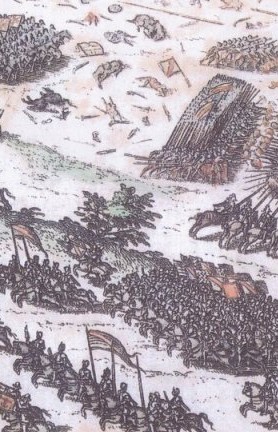

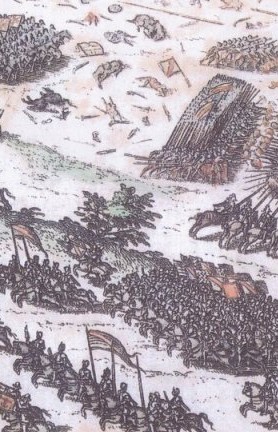

From these contemporary works of art we see the ubiquity of the bend on Protestant flags, on both plain fields and with other geometric symbols, usually horizontal stripes (upper left, from the Taking of Montbrison). From the Battle of St. Denis Tapestry (lower right) we see that while the colours varied, white was always present.

Did Huguenot infantry wear white coats?

At the battle of Moncontour an eyewitness (La Popeliniere) related that the entire Protestant army wore white. Aside from the casaques of the Gendarmes, the infantry, including the Landsknechts, wore their camises (common white shirts) outside their clothes. Yet it would seem they did not as a rule wear white coats. Contemporary art depicts them as dressed variously in the same works wear the cavalry is shown all in white. Le Moyne's drawings of French foot soldiers in Florida don't even have the officers in white sashes (they did not need a fieldsign where there were no French Catholics to differentiate themselves from). The various contemporary tints of the engravings show a wide variety of colours. Aubigne, during his campaign on the Iles D'Oleron in 1586 writes about how he kitted out 200 infantrymen in crimson trousers, to the annoyance of Henri of Navarre whose own men were in rags! He also records that in 1578 all of the Huguenot troops in Languedoc decided to buy the same color coats, and that the officers (who often wore what they chose) were only to distinguish themselves by a chain around their necks as a badge of office.

Protestant involvement in the struggle in the Netherlands under the Duke of Anjou brought a new wrinkle into the issue- the wearing of orange coats and casaques in solidarity with the rebel house of Orange, led by William 'the Silent' of Nassau. Apparently in the 1580's many Protestants were still wearing these coats, including Bethune as mentioned above.

It therefore seems likely that white coats, shirts or field signs were also worn by the infantry, but not as uniformly as the Gendarmes.

The claim that Puritanism made for drab clothing

Again the artwork is fairly clear on this issue, in that it shows Huguenot infantry dressed in the same manner as everyone else. Pluderhosen is quite common on the St. Denis tapestry, in the dozens of engravings of Jacques Tortorel and Jean Perrissin, and in the drawings of Le Moyne in Florida. In 1581 at a synod in Montauban, the ministers issued a denounciation of extravagant clothing, not in fact the first on record (Conde issued a similar one in 1568); this of course shows many were dressing extravagantly. Le Moyne's sketches (later turned into engravings) show pinked and laced coats and trousers with feathered hats.

Austerity was the goal. Striped and coloured lances and vibrant pennons were frowned upon as a way to separate men from each other through ostentation, and the Huguenots prized the concept of the 'Priesthood of the Believers', where no man should truly be elevated above another (although they did not apply this to the existing national social order).

Left to right: Henry of Navarre, Francois de la Noue, and Agrippa D'Aubigne

The use of the white Cross of St. Denis

The white cross had been the symbol of France for hundreds of years before the wars, and had been coming back into vogue at the end of the Italian Wars. However at the massacre of Toulouse in 1562 Catholics had used it as a field sign, making most, but not all Huguenots wary of using it. After the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of 1572 a Protestant assembly at Sancerre banned its use as it had again been an enemy field sign. That began to change after the alliance with the Crown was signed in 1585, and when Henry of Navarre became King Henry IV of France his Protestant soldiers wore it to show that the Leaguers and Guisards were not fighting for France, but against it.

Internet Links to primary resources

Memoires of Maximillian de Bethune, Duke of Sully (In English)

Memoires DE JACQUES-AUGUSTE DE THOU 1553-1617

Memoires of FRANÇOIS DE SCEPEAUX SIRE DE VIEILLEVILLE ET COMTE DE DURÉTAL MARÉCHAL DE FRANCE 1509-1571 (in French)

Memoires DE PIERRE DE L'ESTOILE 1546-1611 (in French)

Commentaires BLAISE DE MONTLUC 1500-1577 MARÉCHAL DE FRANCE (In French)

VIE ET MEMOIRES DE GASPARD DE SAULX, SEIGNEUR DE TAVANNES 1509-1573 (In French)

Memoires of Theodore Agrippa D'Aubigne (In French)

For further reading

'Le Blanc de France. La construction des signes identitaires pendant les guerres de Religion (1562-1629), Denise Turrel

'Recherches sur les drapeaux franc¸ais. Oriflamme, bannie`re de France, marques nationales, couleurs du roi, drapeaux de l'arme´e, pavillons de la marine', Gustave Desjardins

The King's Army, James B. Wood

'The Huguenot Wars, Julien Coudy

Noble Power During the French Wars of Religion: The Guise Affinity and the Catholic Cause in Normandy,

Struart Carroll